What is the first sentence in the Lean whispering game?

Most of us have played the whispering game when we were kids. We sat in a circle and one person started the game by whispering a sentence to the next person. Like in a relay race each person in the circle received the sentence and passed it on to the next person. The game continued and once the sentence had reached the last person in the circle it was spoken out loud. Everyone always laughed since the difference between the first and last sentence was striking.

The Lean whispering game started thirty years ago when John Krafcik wrote the first “sentence” in Sloan Management Review. Womack and his colleagues sat next to Krafcik in the “circle” and passed on the sentence by publishing “The machine that changed the world” which was the first book on Lean. Since then we have continued to play the Lean whispering game in all types of directions. The Lean manufacturing circle is still going strong, but we also have a cascade of new circles playing their own whispering game. We have whispering games going on within different functional settings (e.g. Lean distribution, Lean sales, Lean service, Lean supply, etc.) and we have whispering games going on within different industries (e.g. Lean banking, Lean construction, Lean healthcare, Lean in public sector, etc.).

Lean has become one of the most widely spread management philosophies of all time. Lean is everywhere. From a theoretical and practical point of view, however, the situation is disastrous. The concept has become so diluted that it is today almost impossible to understand what Lean is all about. Who owns the authority to define Lean? What articles and books shall one read in order to understand the essence of Lean?

Toyota in Japan has never played a whispering game

Given this conceptual development of Lean, we think it is of great value to go back to the origins of Lean and shed some light on the “true” first sentence, namely the original definition of the Toyota Production System (TPS). It was, after all, Toyota’s celebrated production system that gave rise to the lean concept in the first place. How does Toyota define Toyota Production System in Japan? Some articles and books have over the years been written about TPS, but most of these are just interpretations mostly based on studies of Toyota outside Japan.

Therefore, we found it necessary to study the original Japanese documents used by Toyota Motor Corporation in Japan, when they are internally defining and explaining TPS for their own employees. After a two-year case study of Toyota Motor Corporation in Japan we were able to identify, access and analyse six documents (in total 164 pages of Japanese text) originating from different internal sources. All documents had been or were currently used within their own management training. When comparing the content of these documents, it was striking that they all used the very same concepts, words and explanations to describe what TPS is all about. Even when comparing with Japanese books, published by former Toyota employees, the definition of TPS is consistent.

TPS was initially called “No debt management”

Two of the documents, we analysed, included the history of TPS, where they described why the concept was developed. According to Toyota, the key event that actually formed the foundation of TPS was the crisis facing Toyota Motor Company in the early 1950ies. The crisis led to the need to dismiss 2,000 workers, which was catastrophic for Toyota. In the aftermath of the crisis the company faced the need to raise money. However, banks and other financial institutes refused them “heartlessly”, which almost forced the company to go bankrupt. Kiichiro Toyoda proclaimed the need to develop a business system, where they “never ever” had to depend on support from banks. He called the philosophy “No Debt Management”. In order to realize the philosophy, it was necessary to:

- Not buy or transport goods (materials) which are not needed immediately.

- Not produce or transport goods which will not be immediately sold.

- Immediately turn products into money.

- Not produce defect goods and circulate them into the manufacturing system.

Taiichi Ohno later realized this philosophy within Toyota’s manufacturing function, and he developed the ideas into the Toyota Production System.

The foundation of TPS is Just-in-time and Jidoka

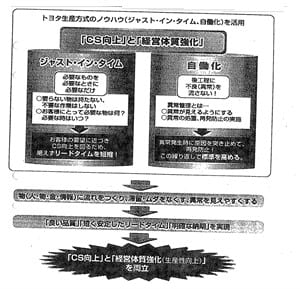

When analysing the six internal documents, all of them have a consistent definition of Toyota Production System. TPS is based on two pillars: Just-in-time and Jidoka. The picture to the right is a direct translation of a picture that is used repeatedly within all documents, describing the purpose and foundation of TPS.

As can be seen in the figure, the purpose of TPS is to increase customer satisfaction and strengthen Toyota’s management capabilities. The focus on customer satisfaction is critical, since it all starts with the need of the customer. However, given the origins of the No Debt Management philosophy, the focus is also on increasing productivity (that is strengthening management capabilities). Toyota is very cost-oriented. They see the market as deciding the price; hence the only way to increase profit is to work with the cost. This leads to the extensive focus on eliminating waste. It is particularly important to raise the productivity of labour; as such improvements are not easily copied.

As can be seen in the figure, increasing customer satisfaction and strengthening management capabilities rests on two pillars – Just-in-time and Jidoka. Understanding these two pillars is fundamental to understanding TPS.

Just-in-time – the ability to continuously improve flow

Just-in-time is obviously well-known to all those interested in Lean and TPS. The sources of Just-in-time can be traced back to the philosophy of No Debt Management and the focus on the customer satisfaction is also clear. The purpose of Just-in-time is to generate flow in a process delivering what the customer wants, when the customer wants it, and just the amount wanted. The company should only make what is needed, no more and no less.

The main focus of Just-in-time is to reduce the lead-time from the customer need is identified (customer order) until the product or service is delivered and exchanged for money (through the customer paying). This lead-time contains both productive time and non-productive time and hence the importance of removing unproductive time. In realizing Just-in-time, Toyota continuously strives to improve flow by decreasing and stabilizing the lead-time within its processes. The optimal state is to have one hundred per cent value-adding time.

This is Lean

Niklas Modig and Pär Åhlström are the authors of one of the most influential Lean books of all time “This Is Lean – Resolving the

Efficiency Paradox”. The book has sold over 250 000 copies and is translated into fourteen languages.

Jidoka – the ability to continuously improving the way of working

The purpose of Jidoka is to avoid processing defects (or deviations from the standard) to the next step in the process. To realize Jidoka it is necessary to thoroughly manage deviations. This means making deviations visible and to handle the deviations immediately and prevent their reoccurrence. Toyota does this by following the following sequence:

- Develop a best way of fulfilling the need, i.e. create a standardized process.

- Visualize the standardized process so everyone can see it.

- Continuously control and manage the progress of the process, in order to see that it is “normal”, i.e. the standard is being followed.

- If the standard cannot be followed (an abnormal state occurs): Identify the root-cause of the deviation and develop a new best way of working, in order to secure that the need is fulfilled in the best way.

Toyota calls this improvement loop for “management of abnormalities”. The goal is to develop an operational system that has an inherent capability to instantly identify deviations from the standardized processes. The deviations are identified through visualization and continuous control of the progress of the process. Once a deviation is recognized, the root cause is identified, and proper countermeasures are undertaken to prevent reoccurrence.

JIT and Jidoka – two sides of the same coin

Even if Just-in-time and Jidoka are defined and treated separately, they are mutually interdependent and can be considered to be part of “one dynamic system”. The two pillars are striving to realize two sides of the same coin. Just-in-time is about understanding the need of the customer and continuously striving to fulfil that need in the best way. Put differently, Just-in-time is about effectiveness – making sure that the company is doing the right things. Jidoka, on the other hand, is about developing an optimal way of working through continuous improvement. Toyota states clearly standardization is the rock the “continuous improvement church” is built upon. Standardization allows everyone to understand what “normal” is, which consequently also allows everyone to understand, what is abnormal. Toyota sees all abnormal situations (deviations) as a possibility to continuously improving their standards. Deviations are the triggers of improvement. In contrast to Just-in-time, Jidoka is more about improving efficiency – making sure that the company is doing things right. Together these two pillars are the engine driving customer satisfaction through continuous improvement.

Printed with permission.

Jidoka – the forgotten part of Lean

What is striking, when comparing Toyota’s own definition of their production system with what has been written on Lean, is how Jidoka has largely been ignored. While the literature is replete with the importance of flow, and how to create it, our contention is that the deeper meaning of Jidoka has largely been misunderstood and its importance underestimated. Jidoka is so much more than merely “stopping the line”, when a defect is noticed. Jidoka is the engine that drives the whole production system. It is the mechanism that develops a conscious and continuous learning system.

When Toyota describes the philosophy underlying Jidoka, they state that it is impossible to manage and control a whole production system. But when the production system is standardized, then it is possible to manage and control “the whole” through managing irregularities, or deviations from the standard. As soon as deviations are detected, problem-solving loops are initiated, often at different levels, to help the system come back to – or improve – the normal state. Flow, or Just-in-time, is nothing without Jidoka, just as Jidoka is dependent on Just-in-time to do the work. It is, after all, a system – the Toyota Production System. And this system and its two pillars is a far cry from the Lean whispering games that are being played in so many different places in the Western world.

![Toyota Production System (bild ) [Skrivebeskyttet ] Rettet](http://effektivitet.dk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ToyotaProductionSystem(bild)[Skrivebeskyttet]rettet_300x225.jpg)